Technical Art History and the Art Historical Thing

Michael Yonan

Art history is the scholarly study of objects and their histories. This was the definition of the discipline presented to me as a student some thirty years ago, and it remains generally true today. One online source offers a nicely succinct summation: “Art History is the study of objects of art considered within their time period. Art historians analyze visual arts’ meaning (painting, sculpture, architecture) at the time they were created.”1

A seemingly benign statement. Yet ponder it for a moment, and its underlying assumptions gradually become more unstable. Art history is the study of objects. Yet a visit to any museum will soon dispel the idea that “objects” define the terrain of art history. The objects selected for presentation in any art museum are but a highly selective subset of human goods, and, it should be added, are usually selected inconsistently. What is the reason for displaying an ancient Greek lekythos and not a mass-produced cruet set from IKEA? The simple answer is that one is art and the other is not, which of course invites the question of how and when something becomes art. The definition above provides its own answer by singling out the classical triumvirate of high arts for special indication. Painting, sculpture, and architecture are the most valued kinds of art, which may seem again incontrovertible until one begins to think about artistry more broadly. Cannot textiles, woodwork, ceramics, and other kinds of objects also be understood as art? Museums house them, too, but these objects seem to operate in a different interpretive space, one broadly characterized as “design.” We might turn to universities for clarification. Peeking around the halls of academia quickly alerts one to the existence of other disciplines also interested in objects and their histories. Archaeology, anthropology, and history are among the more established ones, while museum studies, material culture studies, landscape architecture, design studies, and cultural studies are newer interdisciplinary pursuits that claim some sort of investment in objects. Is art history part of this team, does it overlap with a few, or is it distinct from them?

We can interrogate our definition further by zeroing in on the historical component of the cited definition. Art history considers works of art “within their time period” and therefore isolates visual arts’ meaning “at the time they were created.” These phrases are telling. They reveal that art history is concerned with a primary kind of meaning for its objects, one associated with a specific moment—its making—that is valued above other potential meanings an object can bear. This has the effect of elevating a single moment in an object’s life over others, and moreover implies that works of art have a dominant meaning that takes precedence. Our definition also implies that the art historian’s job is to recover that meaning and make it intelligible. Such a definition is artist centered in that it privileges the artwork’s maker. This framework reasserts the image of a lone genius creator, a central figure in art history, and further characterizes the work of art as a kind of puzzle awaiting deciphering.

Perhaps it is too obvious that this definition is a straw man. The range of art historical practice today is much wider than what it describes, and more sophisticated definitions of art historical practice certainly exist.2 But its general contours still seem true, insofar as much art history remains tethered to its terms. Art history continues to be a highly selective form of object analysis, choosing to analyze objects that possess value historically, aesthetically, or both. It also remains, pace Roland Barthes, very much a discipline structured around known and named artists, who function authorially to communicate through their art. These qualities give art history, for all its current diversity, something like a shared set of concerns and priorities.

The problems involved in describing what art history is, versus what it might become, lie at the heart of this essay, which attempts to sketch out the potential place of the object in our discipline: the thing of art history. This seemingly simple task—defining what it is we study—is actually one of the most inconclusive and destabilizing acts for the scholar. We study many different things and do so from many different perspectives. What definition could possibly encompass everything from ancient pottery to contemporary video art? The answer, I have suggested elsewhere, is materiality, and through the explorations of materiality pursued in interdisciplinary material culture studies we might find tools for fine-tuning that definition.3 What I will argue in this essay is that the art historical object needs to be understood in quite literal terms as a thing, as matter, and that technical art history can play the role of bringing that thingness into greater prominence. To give away my conclusion, without the kinds of knowledge gained from technical art history, art historians will never really understand their objects and will forever divorce them from material culture. The object of art history will remain a spectral entity and not a finite thing with specific material characteristics upon which meaning can be built. Yet achieving this, paradoxically, means letting go of the received ideas about what constitutes an object’s historical context.

If art history warrants a basic definition, so does technical art history. We can understand it as the process of using technical means to study works of art. These can include laboratory-based procedures that permit better understanding of an artwork’s physical qualities, or more roughly the application of scientific procedures to art. Technical knowledge has traditionally been the purview of museum conservation departments—technical knowledge pursued for purposes of preservation. That is certainly an application of it to good ends, but technical knowledge has many additional benefits.

As Emma Jansson proposes in her essay, technical art history can help refine the imprecise language of art historical and art theoretical description, something sorely needed as art historical terminology is often surprisingly inexact. “Oil on canvas” is a designation for thousands of paintings hanging in the world’s museums today. The uninitiated might think that this indicates consistency across time and cultures, yet the range of materials that might actually fall under this description is wide, since the precise composition of canvas, for example, is not the same across time. Scholars invested in technical art history have long known this, but the broader art historical community has not yet fully incorporated knowledge of this kind into the formation of historical interpretations.

Technical investigations can also shed light on historical matters that would seem more the purview of the researcher than the scientist. A recently published example illustrates how technical knowledge can open up new historical knowledge. The furniture collection of the Swedish Royal Court (Kungliga Hovstaterna) in Stockholm houses two eighteenth-century pieces attributed to the Swedish cabinetmaker Nils Dahlin (c. 1737–1787), a writing desk and an étagère or display cabinet, both dating from 1771 (Fig. 1). Incorporated into their design are panels made of lacquered wood originating in East Asia. Based on traditional methods of visual and stylistic analysis, scholars formerly surmised that Dahlin’s pieces were constructed from a Japanese screen imported to Sweden and then cut up to create the panels used in the furniture. It was further thought that some of these pieces were left over from wall decorations in the Chinese Pavilion (Kina Slott) at Drottningholm Palace. A series of technical investigations recently confirmed that the mixture of saps used in the lacquered panels of the desk show affinity with lacquers deriving from the Ryukyu Islands of southern Japan, suggesting that they originated there.4 The étagère panels likewise indicate an Asian origin, but one less precise than that for the desk: the lacquer used on them contains elements from trees that grow in Vietnam, which were combined with others from northeast Asia, either China, Japan, or Korea. This also supports the possibility that the panels are Ryukyuan in origin, since political control of the islands had shifted in their early modern history from Ming China to Shimazu Japan. Workshops from across this region combined techniques and materials. This same technical investigation disproved the supposition that the panels are leftovers from the Chinese Pavilion, since the chemical composition is different from the lacquer used in that project.

Pinpointing a Ryukyuan origin for the panels in Dahlin’s furniture tells us something important: of what they are actually made. The knowledge gained replaces a generic designation of “Asian” or “Japanese” lacquer with something considerably more precise. This is information that the naked eye, even that of a highly knowledgeable connoisseur, could probably not determine on its own. But more excitingly than that, the technical analysis gives a glimpse into a cultural situation that otherwise is virtually inaccessible. We get a sense, however remote, of workshop practices in a part of the world (the Ryukyu Islands) not central to commonplace art historical narratives, practices for which the written record is spotty at best. Moreover, beyond recognizing that examples of Dahlin’s furniture are hybrids of Asian and European design, we learn that the Asian components are themselves products of cultural exchange across the East China Sea, in other words, that they were hybrid objects even before Europe entered their history. These are layers of historical meaning and possibility that open up an understanding of these objects not accessible via other means. Recognizing this further disturbs the simple idea that the furniture was made by Dahlin; he is a maker, but just one of several whose labor contributed to the final objects.

When scholars now subject this desk and étagère to more elaborate processes of interpretation, asking about their semantic potentialities, they can do so with a firmer understanding of what they actually are. This is an important point because art historical practice has evolved into a highly theoretical undertaking, particularly since the cultural turn of the 1970s, which introduced what were then called “new perspectives” to art historical study. These are the well-known pantheon of approaches that includes feminist art history, the social history of art, Marxism, psychoanalysis, and more recently queer, postcolonial, and poststructuralist perspectives. In tandem, these theoretically oriented approaches have greatly multiplied perspectives that scholars can bring to what they study. The advantages to this diversity are beyond question. It has resulted in an exponential multiplication of art historical meanings, as many diverse readings of works of art take place simultaneously and many conflicting interpretations coexist.

I do not wish to suggest that there is anything wrong with this interpretive richness. But it requires grounding in the objects themselves lest the interpretation take on a life of its own. All art interpretation emerges from a dialogue, a back-and-forth between the interpreter and the artwork. However, it is an elusive dialogue in that distinguishing input from interpreter and from object is never easy to characterize.5 For example, we can look at the social history of art and its reliance on the concept of ideology as a structuring concept for describing how works of art convey meaning in society. Thinking about ideology can take the interpreter down several related paths. The work of art can be defined as promoting a specific ideology associated with the class structure of its historical moment, for example. The notion of art itself is also ideological: how we understand what art is, its process of becoming art, is deeply embedded in ideological concerns. One could continue in this way for a long time. The ideas themselves have a seductive power, and that power generates its own momentum. They can be so directive and urgent that, gradually, they loosen the interpreter’s attention away from the object, which is supposed to be art history’s focus and which rarely fits an interpretive paradigm totally. Objects push back against easy transformation into ideas.6 There is also a narrative dimension to art historical interpretation. Art historical methods are not just ways of deriving meaning: they are literary forms, really subgenres of art historical writing. An essay that interprets a work of art according to feminist art historical principles will follow certain interpretive paths, and those paths are to some degree predictable. The most extreme version of this idea would be to say that all art history is really a kind of fiction, a literary form based in narrative structures about people and objects. While I do not necessarily think this true, it does seem true that some art interpretation slips into a kind of storytelling.

My point is that creating historical narratives about art can actually distract from the object itself as a thing, which exists not in historical space at the moment of interpretive encounter, but in the interpreter’s contemporary, temporally experienced space. Mona Lisa may be a painting made by Leonardo da Vinci in Italy around 1505, and art historians may wish to understand it through that time, place, and person. Yet we know it today as a contemporary object in Paris. What we see is not only the object Leonardo made, but also an object that he began that has since been modified and recontextualized endlessly, both in the actual physical materials that constitute it and via its image, reproduced constantly, altered shamelessly, and distributed around the globe. Making sure we know what we are interpreting, and being honest about it, is one of the great challenges to undertaking art history today. At issue here is the question of where to draw the line between creating knowledge about an artwork’s originary moment and recognizing the interpreter’s experience of it today. Both are part of the art historical encounter. The object/context divide demands constant repositioning, as a tension between the two is inherent to the study of all art. It can never be fixed unilaterally in a way that applies everywhere, even as much as art theory may wish to describe it in universal terms.

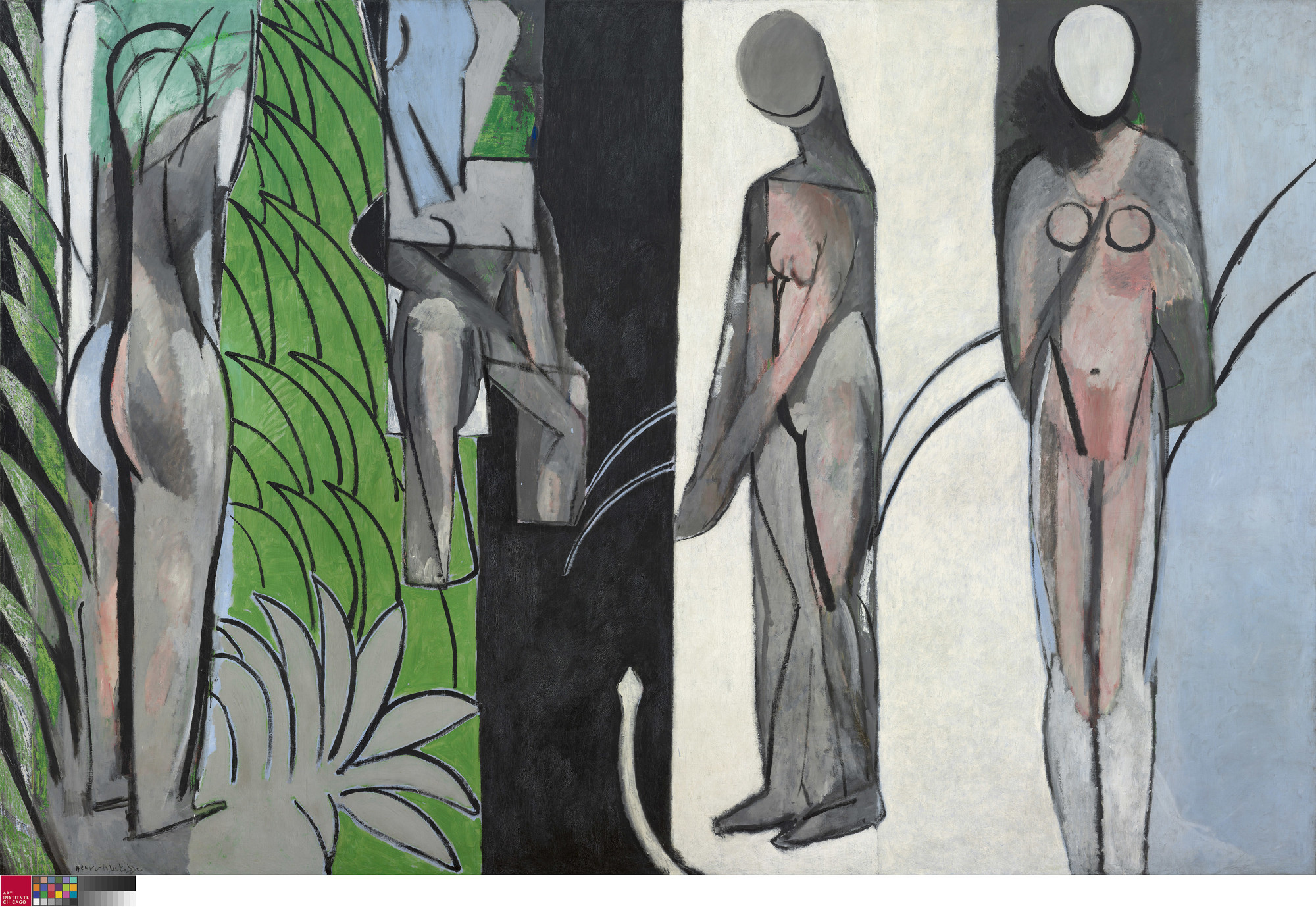

To illustrate this point, let me tell a story of my own. The last conference I attended before the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated in spring 2020 happened to take place in my hometown—Chicago—and one afternoon I escaped the conference in order to visit the Art Institute, a museum that has been part of my life for over forty years. One picture I particularly love looking at is Henri Matisse’s wonderful Bathers by a River, begun in 1909 and worked on intermittently by the artist until 1917 (Fig. 2). As a student, this painting fascinated me. Why, I wondered, did Matisse keep returning to this canvas over such a long time, and why did he change his mind so frequently about what he wanted it to be? Returning to it again after many years, I saw some things in Matisse’s painting I had never noticed before, like how thinly the paint is applied on many parts of its surface, how rushed it seemed despite its long gestation time, and, for lack of better descriptors, its audacious crudeness. My looking reaffirmed how wonderful this painting is as an object, how it delights in creating patterns of shape and color that it simultaneously subverts, and how much creative brio is visualized on the canvas through the brushy traces of that process.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2The Art Institute recently included Bathers by a River in a series of Instagram videos highlighting prominent works from its collection.7 In the post, they proposed an interpretation of the picture based on it being made immediately before and during World War I. Matisse’s efforts recorded the artist’s foreboding and indecision due to war. They even interpreted its color palette—a combination of gray, black, and a vivid shamrock green—as creating a tense, uncomfortable mood. And the headless, mannequin-like figures they likewise interpreted as stony sculptures devoid of humanity. The painting comes to illustrate a tense emotion that fits an understanding of the historical moment in which it was produced.

This interpretation annoyed me, frankly. Not because it does not fit Matisse’s picture, since as a way of understanding it, it was perfectly viable. But it seemed to me a historically determinative way to read the picture, one that minimized what could be said about its materiality, and that was done in the service of making the story behind this painting fit a simplistic understanding of historical context. It also negated my personal joy in looking at it. The post raised a gnawing question for me: why must works of art always be explained through evocation of historical setting? Could there be another way of understanding what Matisse tried to do in this picture that did not make it a reflection of the conditions in which he made it? My own viewing of the picture suggested that this was possible, but somehow the urge to contextualize had taken the museum down a different track. By insisting on historical context as the primary framework for interpreting Matisse’s picture, the preparers of that post missed many of the things about it that have made it so compelling to me. And many of those things are, in fact, embedded in its materiality. That materiality may seem too complex for the average museum visitor to comprehend and therefore not be prioritized in social media posts like this. Yet my sense is that some visitors want to know the science behind the image, so to speak, and would find that kind of information illuminating and aid in comprehending the art.

The Art Institute has produced an exemplary technical report on the painting that demonstrates vividly what technical analysis can reveal about an object’s history.8 But if we expect the results of technical studies to correlate with established historical trajectories, the impact of such technical knowledge will be lessened. What the many changes to this picture confirm is that Matisse was searching for something, that he was trying to reconcile his work with influential developments in art making, Cubism especially, and also to work through some of his own concerns about what his art would be. That he left so many of the brush marks of this search visible on his canvas says not that he was interested in a loose painting style, but that he wanted his efforts to be seen, to become part of the experience of the picture. That this happened during the ramping up to war is certainly part of the painting’s history, but it is not in fact inherent to the object itself. Rather than find traces of a darkening Europe here, maybe we can see instead Matisse’s investment in his own artistic growth and change. There is beauty in his efforts that a simple art-in-context interpretation misses.9 Recognizing that beauty requires engaging with Matisse’s painting as an object, while avoiding over-investing in what it represents as an image.

By way of a conclusion, I want to suggest that art history consider replacing some of its better-known interpretations of art with new ones rooted in the materiality of art itself. This would be more than object biographies, stories of how an object passes through different hands over time and takes on new meanings. Rather, it would be a history of an object as a changing set of material conditions that explain how an object’s materiality operated at different moments in time, or, to use Emma Jansson’s terminology, how objects are “composite structures” with internal as well as external histories. The advantage to this would be to make the artwork an active agent in the construction of its history, not a reflection of that history or of the interpreter’s priorities. It seems to me that art historical methodology sometimes asks too much of historical context, forcing it to take some of the work out of understanding an object by reducing it to a vessel defined by historical conditions. By grounding interpretation in the materiality of an object, by seeing it as the literal matter that it is, we might avoid the pitfall of making context into an object’s meaning. Doing so would propel us to trust more in what is actually there, rather than transforming the art object psychologically into what we wish it to be. And I would suggest that this would be impossible without the kind of deep material understanding that technical art history can offer. What the work of art actually is needs to be built into the process of interpreting what it might mean.

Author Bio

Michael Yonan is Alan Templeton Endowed Professor of European Art 1600–1830 at the University of California, Davis. His most recent publications are Messerschmidt’s Character Heads: Maddening Sculpture and the Writing of Art History (Routledge, 2018) and Eighteenth-Century Art Worlds: Global and Local Geographies of Art, which he co-edited with Stacey Sloboda (Bloomsbury, 2019). He has also written several essays that explore the place of materiality in art history.

Notes

https://www.iesa.edu/paris/news-events/art-history the website of International Studies in History and Business of Art and Culture, a Paris-based school offering instruction in cultural events management and the art market. ↩︎

For example, that provided by the Khan Academy’s Art History course: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/approaches-to-art-history/approaches-art-history. ↩︎

Michael Yonan, “The Suppression of Materiality in Anglo-American Art-Historical Writing,” in The Challenge of the Object/Die Herausforderung des Objekts: Proceedings of the 33rd Congress of the International Committee of the History of Art (CIHA), Nürnberg, 15th–20th July 2012, ed. Georg Ulrich Grossmann and Petra Krutisch (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2014), 1:63–66. ↩︎

Maria Brunskog and Tetsuo Miyakoshi, “A Colourful Past: A Re-Examination of a Swedish Rococo Set of Furniture with a Focus on the Urushi Components,” Studies in Conservation, December 11, 2020, [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00393630.2020.1846359]{.ul}. ↩︎

Something suggested in T. J. Clark, The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008). ↩︎

Carol Armstrong, response to the “Visual Culture Questionnaire,” October 77 (Summer 1996): 27–28. ↩︎

Art Institute of Chicago (@artinstitutechi), “Henri Matisse’s Bathers by a River,” Instagram, August 31, 2020, accessed February 22, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CEj4YoIpXe3/. ↩︎

Bathers by a River, in Matisse Paintings, Works on Paper, Sculpture, and Textiles at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Stephanie D’Alessandro (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2019), cat. 25, https://publications.artic.edu/matisse/reader/works/section/61/61_anchor. ↩︎

This is closer to the analysis of the picture provided in the catalogue accompanying a major exhibition on this period of Matisse’s career organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art: Stephanie D’Alessandro and John Elderfield: Matisse: Radical Invention, 1911–1917 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010). ↩︎